Chapter outline

The skin and the oral mucosa share a lot in common because of a shared lineage from ectoderm and mesoderm. Both are composed of a stratified squamous epithelium, and just deep to that areolar CT, followed by dense irregular CT. Unfortunately, parts of the skin and oral mucosa received different names and are classified differently, based on their location. That means you have more names to memorize... Boo!

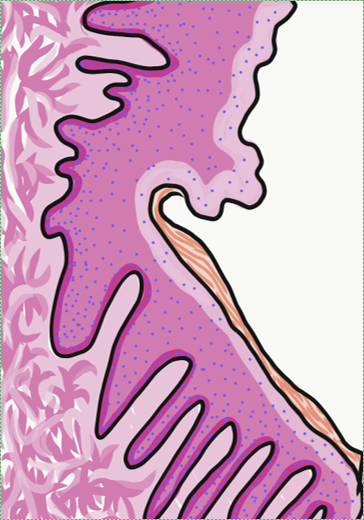

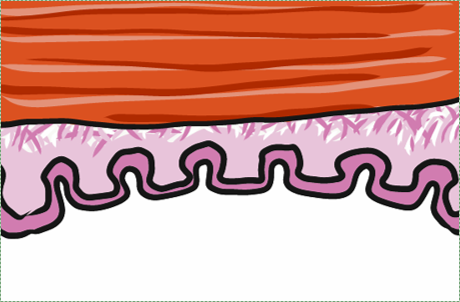

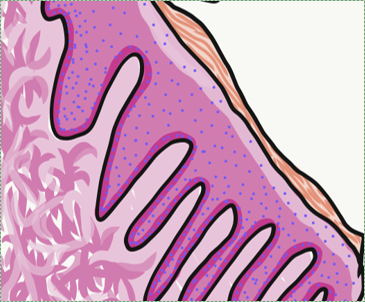

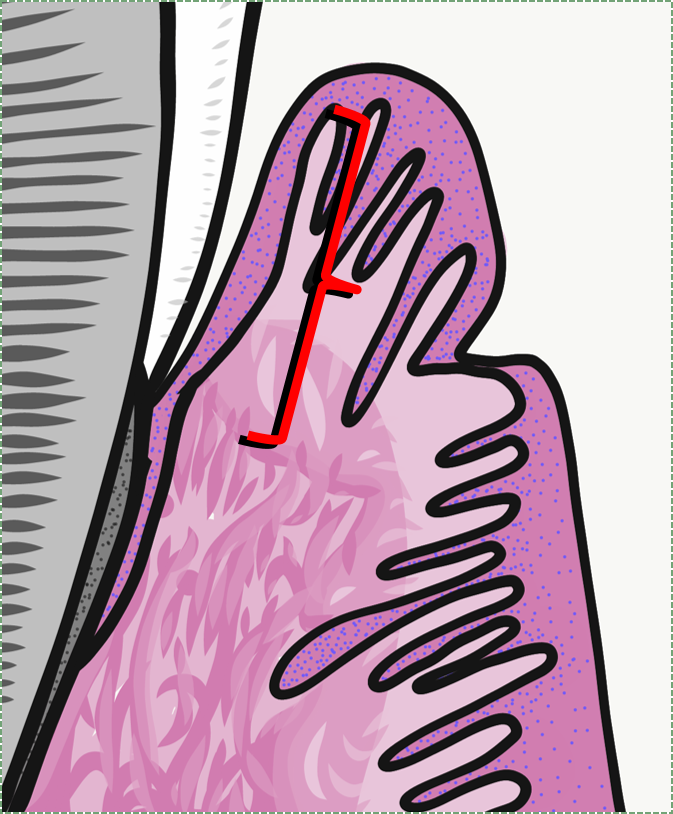

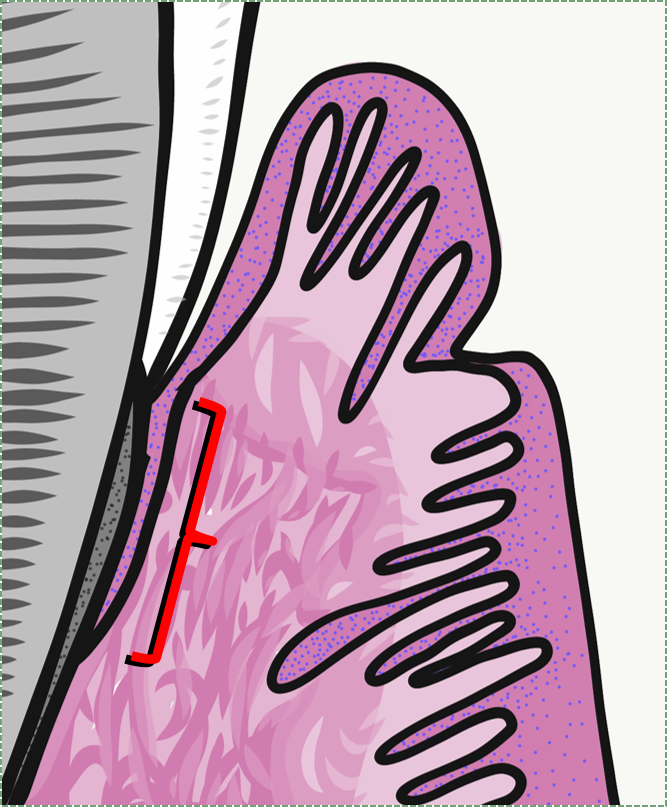

The dermis is the connective tissue layer of the skin. It is composed of a layer of dense irregular CT, the old-fashioned name for which is the reticular layer of the dermis. The layer of areolar CT has an old fashioned name, too, the papillary layer of the dermis. It received that name for having finger-like dermal papillae on its apical surface, compared to the smoother transition between it and the reticular layer. In this image, the upward-pointing dermal papillae meet downward-pointing rete pegs of the next layer, the epidermis. The epidermis is composed of stratified squamous epithelial tissue. The dermal papillae of the dermis meet the rete pegs of the epidermis like inter-meshed fingers from two hands, which makes for a stronger connection between epidermis and dermis. Some regions of the oral cavity won't require such a strong connection, and the rete pegs and dermal papillae will be smaller or absent. Note that the border between epidermis and dermis is distinct, whereas the border between the reticular and papillary layers of the dermis is blended. That is because the epidermis is derived from the ectoderm, while the layers of the dermis are derived from the mesoderm.

The epidermis of the skin is highly keratinized. The epithelial cells make a large protein called keratin, which is somewhat similar to collagen, except keratin is not secreted. These long fibers accumulate within keratinocytes, the principle cell of a stratified squamous epithelium. As keratinocytes mature, they get pushed towards the apical surface by dividing stem cells in the deepest (basal) layer. As the keratinocytes move supferficially, they fill up with keratin, and receive fewer nutrients (remember, an epithelium is avascular), until ultimately all the keratinocytes at the surface are dead and completely full of keratin. The keratin fibers are cross-linked to each other and to desmosomes, which anchor the dead cells together, making for a very tough and water-resistant barrier. Keratinized regions of oral epithelium are located where there is a lot of abrasion. In the rest of the oral cavity, we want moisture, so there will be less or no keratinization.

| pigment | color | source |

| Melanin | red or brown/black | melanocytes |

| Carotene | orange-yellow | diet (plants) |

| Hemoglobin | Red-maroon | Blood |

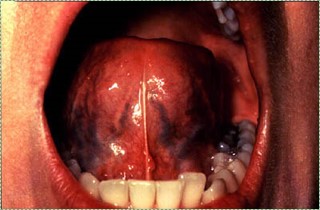

There are 3 major pigments that contribute to skin color, listed in the table. Keratin has no color, but it can obscure the visibility of the deeper pigment hemoglobin. Melanin levels show the greatest amounts of variation in the skin of different people. One major function of melanin in the skin is to absorb UV light, which can reduce damage to DNA, thereby reducing skin cancer. Melanin also protects folic acid levels, which can be destroyed by UV light. Because folic acid is required for cell division, low levels during pregnancy can lead to birth defects of the neural tube. Melanin may also be present within the oral cavity, despite the fact significantly less UV light reaches there. Another function of melanin is to resist damage from abrasion, which is why it may be found in higher levels in the attached gingiva. Similarly, pregnancy leads to an increase in the amount of melanin in the areolas and labia minora. Melanin is made by melanocytes found in the basal layer of the epidermis, and it is packaged up and given to keratinocytes. Melanocytes are derived from neural crest cells, and are not epithelial by lineage.

Hair follicles are important because they share developmental processes with teeth. That gives these two appendages of the skin an oral mucosa the same basic shape and pattern, only one makes a bunch of keratin and the other calcium hydroxyapatite. A hair follicle is an invagination (an inward-folding) of the epidermis. The stem cells in the basal layer of the hair follicle divide, differentiate into keratinocytes, and eventually die to form the hair itself. A hair, therefore, is an epithelial structure. Sourrounding-- or deep to-- the hair follicle are the connective tissue layers of the dermis.

Where and when hair follicles invaginate from the surface epidermis is regulated by Planar Cell Polarity signals, which ensure more-or-less even spacing between follicles. Similar signals govern the spacing of the teeth. Also similar the teeth, new hair follicles grow beneath old ones, pushing the old ones out in a process called exfoliation. Of course, hair follicles grow and exfoliate more times than your average tooth. Nevertheless, it might be a good idea to keep scientific developments in the hair-loss treatment industry somewhere on your radar, advances there may have applications in some future tooth-growth industry.

The oral mucosa shares the same lineage as the skin. Therefore, we see the same tissue types in the same order. However, because it looks a little different and is in a different location, the layers get different names and are classified differently. Based on the 3 major embryonic tissues, the layers of the skin are classified appropriately, but the oral mucosa is divided incorrectly.

| Skin | Oral mucosa | ||

| Epidermis | Stratified squamous epithelium | Stratified squamous epithelum | Oral mucosa |

| Dermis | Areolar CT | Areolar CT | |

| Dense irregular CT | Dense irregular CT | Sub-mucosa | |

| name | level of keratinization | location |

| keratinized | fully | Skin |

| ortho-keratinized | partially | Masticatory mucosa |

| para-keratinized | ||

| non-keratinized | none | Lining mucosa |

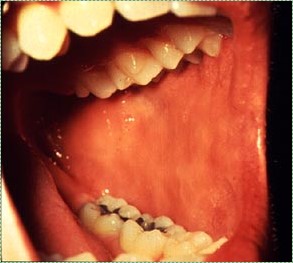

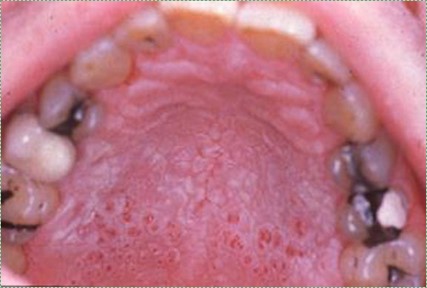

Labial mucosa and buccal mucosa both have a non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelial layer. This gives them a more reddish or pinkish appearance. As with all oral mucosa, there are no hair follicles, but in places sebaceous glands can grow, forming yellowish bumps named Fordyce spots. As a lining mucosa, the epithelial layer is generally non-keratinized, but there can be regions of keratinization where stress occurs. Most noteably is the Linea Alba (or "white line"), running along the line in the buccal mucosa where the teeth meet.

The ventral surface of the tongue and the floor of the mouth both contain very thin, non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. The thiness gives these surfaces a more reddish-appearance than other lining mucosa. The thinness of the epithelium, coupled with the rich blood supply in the deeper lamina propria are also why some medications can be given sub-lingually.

T he soft palate is lined by a non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, with a very thin layer of sub-mucosa deep to it. This gives the eipthelium a firm attachment to deeper muscle tissue, which is important for speech and swallowing.

Alveolar mucosa is lined by a non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. It has a rich blood supply and numerous elastic fibers within the lamina propria, but few dermal papillae and rete pegs.

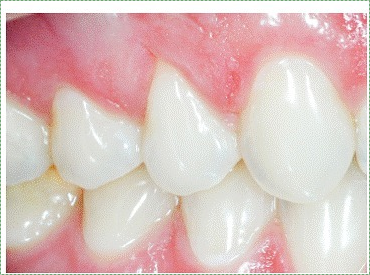

The attached gingiva are a type of masticatory mucosa, lined with a para-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. The increased amount of keratin, compared to alveolar mucosa, obscures the unerlying blood supply, creating a more white-ish appearance.

Interdental gingiva are similar to the attached gingiva.

Marginal gingiva are similar to the attached gingiva.

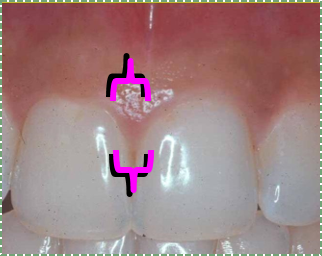

Sulcular epithelium (or crevicular epithelium) is lined by either a non-keratinized or para-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. It creates a space between the gingiva and tooth, named the gingival sulcus, but is not attached to the surface of the tooth. The sulcus is filled with gingivo-crevicular fluid (GCF). This fluid is in essence saliva, but secretions from the junctional epithelium will make it slightly different. Gingivitis leads to inflammatory molecules and white blood cells entering GCF, therefore taking small samples of this fluid is a diagnostic tool for measuing gingival health. The absence of dermal papillae and rete pegs indicates this tissue gets very little abrasion.

Junctional epithelium is a non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. It is special in that its apical surface attaches to the tooth by way of hemi-desmosomes. All other epithelia attach to connective tissue only on their basolateral surface, and their apical surface faces the external environment. This unique attachment to the tooth surface is referred to as the epithelial attachment.

Junctional epithelium is thinner than other gingival mucosa, only 5 cells thick at the end. It is are also more permeable, having fewer desmosomes between cells. This allows white blood cells from the underlying vascular sub-mucosa to migrate through junctional epithelium and enter the gingival sulcus. But this also increases the potential for oral cavity bacteria to do the same in reverse, especially if the epithelial attachment is lost.

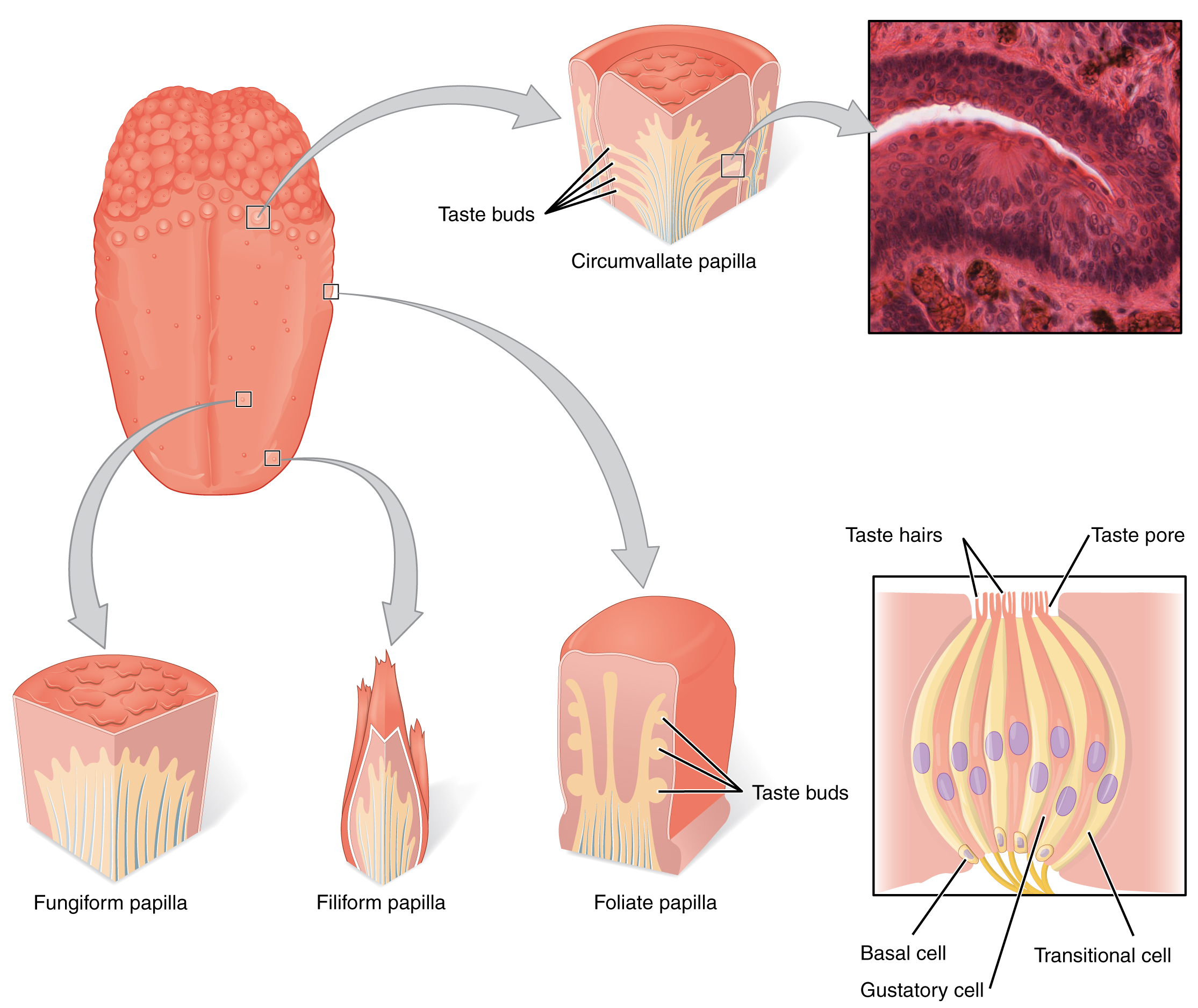

The dorsal surface of the tongue contains more than one type of mucosa. The epithelial surface is mostly an ortho-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, and can therefore be thought of as a masticatory mucosa. Lingual papillae, on the other hand, contain a specialized mucosa-- neither a lining mucosa nor a masticatory mucosa. These structures are appendages of the oral mucosa. Instead of growing inwards by invagination like a hair follicle, they grow outwards. They have either an ortho-keratinized or para-keratinized epithelial layer.

Fungiform papillae contain an ortho-keratinized or para-keratinized epithelial layer over a highly vascular sub-mucosa, giving these structure a more reddish-appearance than neighboring filiform papillae. The epithelial layer contains taste buds, which detect the sense of gustation, which is in turn a part of the perception of taste.

Foliate papillae are found on the lateral edges of the tongue. They also contain an ortho-keratinized or para-keratinized epithelial layer with taste buds.

Circumvallate papillae are found at the border betewen the anterior and posterior portion of the tongue, the sulcus terminalis. They also contain an ortho-keratinized or para-keratinized epithelial layer with taste buds and minor salivary glands.

| Epithelium | Turnover time (days) |

| Skin | 27-38 |

| Hard palate | 24 |

| Floor of mouth | 20 |

| Buccal and labial mucosa | 14 |

| Attached gingiva and taste buds | 10 |

| Junctional epithelium | 5 |

The time it takes to replace all of the cells within the epithelial layers of the skin and oral mucosa is shown to the left. As you can see, the oral epithelium grows quickly, which means it can regernate quickly following injury. This is largely due to the presence of growth factors in saliva. This also means that oral cancers are relatively rare in the absence of large doses of carcinogens (tobacco and alcohol). The epithelial cells of oral mucosa do not live long enough to acquire the multiple mutations to oncogenes and tumor-supressor genes required to cause cancer.

Hyper-keratosis is a homeostatic response of the oral mucosa to stress-- either chemical or physical. In reponse to stress, epithelial cells create more keratin, causing an increase in the degree of keratinization. Vitamin A deficiency can lead to generalized hyper-keratosis. If the increase in keratinization is localized, it is referred to as leukoplakia.

Inflammation of any tissue is referred to as tissue-name-itis, hence gingivitis is inflammation of the gingiva, while periodontitis is inflammation to the gingiva and deeper tissues such as bone. The redness, swelling, heat and pain symptoms indicate the body has suffered trauma, and is undergoing a reponse to that trauma. Mucosa exude more liquid into an area as a part of the inflammatory process, making that region of the oral mucosa larger and paler when inflamed. Ideally, an inflammatory response will limit the spread of the intial damage and set the stage for regeneration. When a tissue regnerates, stem cells will migrate into the affected area, divide, and differentiate into the cells needed to repair the damage, such as keratinocytes or fibroblasts.

Chronic inflammation, on the other hand, can lead to cell death and the loss or recession of a tissue. This is because stem cells generally halt progression through the cell cycle until the inflammatory process removes the source of the stress. Without stem cells generating new cells, chronic stress allows everyday wear on a tissue to accumulate.

With periodontal disease, gingival tissues can become inflamed. With inflammation comes increased amounts of fluid (edema) in the ECM of connective tissues in the lamina propria and sub-mucosa, as well as increased amounts of fluid inside the epithelial cells of the oral mucosa. This in turn causes the marginal, attached and inter-dental gingiva to become visibly swollen. When marginal gingiva are swollen, it may produce a crescent-shaped edema known as a McCalls festoon.

Hyperplasia means the increased growth of a tissue. Gingival hyperplasia is an abnormal growth of gingival tissue. It may look similar to edema, but the underlying cause (and therefore treatment) may be different. It can be a side-effect of certain medications, such as phenytoin and cyclosporine, although other triggers exist. Like edema, gingival hyperplasia can be caused by poor oral hygiene. The first reponse of the immune system to oral microorganisms is inflammation (and therefore edema). Over time, the immune system may repond to stress by releasing growth factors that trigger increased cell division by nearby stem cells. This would be a perfectly normal response in the palms of the hands or soles of the feet, generating a callus in response to physical stress. However, the body sometimes has trouble distinguishing between physical stress and other types of stress, in this case, chemical stress caused by toxins produced by microorganisms.

The gingiva of a patient may or may not exhibit visible levels of melanin. This does not represent any homeostatic change (hence, it is not a clinical change) to the body, and is strictly a cosmetic variation.

Chronic inflammation of the gingiva can lead to gingival recession, exposing deeper tissues of the tooth, which in turn will hasten tooth decay. The most common cause of gingival recession is gingivitis and periodontitis. Gingival recession can also be caused by abrasion (improper tooth brushing), abfraction (bruxism), improper tooth position, and aging.

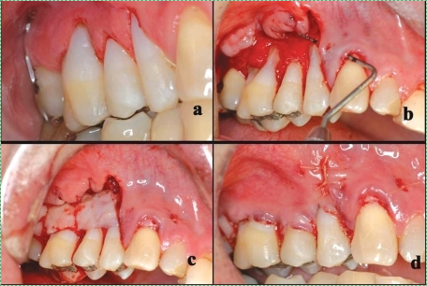

Sub-epithelial grafts splice connective tissue from nearby regions of healthy gingiva (such as from neighboring gingiva or soft palate). This leaves behind small wounds, which heal quickly. Nevertheless, damaging healthy tissue is not optimal. Because the connective tissue used in such a procedure is mostly collagen fibers, another option is a pericardial patch procedure. Rather than using the patient's connective tissue, connective tissue that surrounds a cow or pig heart (the pericardium) can be used instead, after it has been stripped of any pig or cow cells. This a-cellular tissue will not trigger tissue rejection (collagen is collagen), but it acts as a scaffold. Ultimately, the patients own epithelial stem cells migrate over the scaffold to regenerate the oral mucosa. In addition, the patients mesenchymal stem cells migrate into the scaffold from nearby healthy sub-mucosa , and replace the cow or pig collagen. This procedure is very similar to different types of bone tissue grafts. I hope you appreciate the amount of histology and cell biology required to understand how pieces of cow hearts can be used to repair damaged gums.

For futher information:

| FDA information on GINTUIT |

| Osteohealth Mucograft - currently being acquired by another company |

| Gengigel Hyaluronic Acid gel |

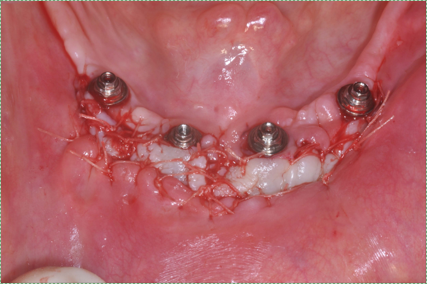

The depth of a periodontal pocket can be measured using a calibrated probe. In a healthy state, the distance from the marginal gingiva to the epithelial attachement should be between 1-3mm. Pockets within this range typically have an intact epithelial attachment, which prevents oral bacteria from entering the sub-mucosa and causing gingivitis or periodontitis. Poor oral hygiene, however, can lead to increased levels of oral bacteria within the periodontal pockets. Because the junctional epithelium is more permeable than other regions of the oral mucosa, white blood cells come into contact with this bacterial population and trigger inflammation. With chronic inflammation comes a loss of junctional epithelium, which can reduce the thickness of the junctional epithelium even further and cause a loss of the epithelial attachment. At this point, the pocket is said to be lined with pocket epithelium. Since it is no longer attached to the tooth, the probe can likely be inserted over 3mm. The thinness of the pocket epithelium brings the probe closer to blood vessels in the lamina propria, making it more likely to damage these vessels, causing Bleeding on Probing (BoP).

It is possible that a periodontal pocket deeper than 3mm could have junctional epithelium with an intact epithelial attachement. These would exhibit minimal Bleeding on Probing, and can be considered uncharacteristically deep pockets rather than a clinical manifestation of periodontitis.

Geographic tongue is a condition where the filiform papillae on the dorsal surface of the tongue become non-uniformly hyper-keratinized, giving some filiform papillae a more white-ish appearance. The pattern of keratinized versus partially-keratinized papillae can change over weeks. The result is stricly of cosmetic concern. There are currently no treatments for geographic tongue.

Black hairy tongue occurs when filiform papillae shed epithelial cells more slowly, thus the papillae become enlarged. This also allows them to pick up more stains from tobacco smoke, foods, or oral bacteria, creating thicker, darker bumps on the tongue. It is thought that this condition might be triggered by overgrowth of certain oral fungi, possibly following the loss of competition with the use of certain antibiotics. The reason the filiform papillae appear hair-like is that both the filiform papillae and a hair are composed predominantly of dead keratinized epithelial cells. Patients are usally encoruaged to brush their tongue when brushing their teeth.